Several years ago I started my first job as a “senior” Go developer. You see, after a modest 3 years in the industry, my arcane ability to use the Go standard library’s strings.Contains() function managed to leave a powerful impression on the hiring team.

Yup, as a senior developer only a few years out of college with no kids and a 6 figure salary, life was looking pretty easy. Well, it would have been easy. It would have been easy if the mind-numbing, gelatinous, corporate goo known as Java (it runs on billions of devices btw) hadn’t chipped away at the once great minds of my new colleagues.

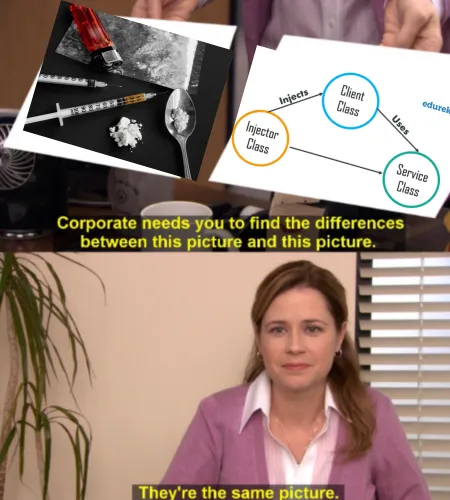

We’re going to talk about my struggles with unit tests at this new company. And mocks. And heroine injections. Erm, I mean dependency injections. (but tbh both are just as bad for you)

BUT… before we do that, let me tell a quick story to give you some context about this new job.

“Fixing” Go 🔗

I’m not thirty minutes into my new job (still brew installing a bunch of nonsense), when a coworker (let’s call him “Bill”) spins around and says:

Bill: “You’re the new Go guy right?”

Me: “Yup!”

Bill: “Ugh, Go is the worst. Luckily for you, I fixed Go’s biggest problem!”

Me: (puckers for safety)

Bill: “I’ve re-added try/catch to the language! No more

if err != nil!”

Take a look at the elegance of Bill’s new language feature:

func main() {

tryCatch(

func() {

panic(errors.New("I'm scared"))

},

func(err error) {

fmt.Println("Caught:", err)

},

)

}

Wondering how Bill achieved this level of syntactic sugar? Super easy. Barely an inconvenience. Just bastardize the panic, recover, and defer keywords.

func tryCatch(fn func(), catch func(err error)) (err error) {

defer func() {

if r := recover(); r != nil {

err = r.(error)

catch(err)

}

}()

fn()

return

}

Running some tests 🔗

After a riveting discussion with Bill about the virtues of “errors as values”, I was able to dive into my first (sigh) Jira ticket.

I needed to implement a new feature on an existing backend Go service. I ran a few commands to get up and running:

$ git clone

Got the code.

$ go build

Good, the main branch compiles.

$ go test

--- FAIL: TestDatabaseConnection (0.00s)

database_test.go:23: dial tcp [::1]:5432: connect: connection refused

Darn, the tests failed. That’s odd, someone must have committed some broken code. Wait…

Why are my unit tests trying to connect to a database server???

Me: “Hey Bill, do I need to set up a local Postgres server to run the tests?”

Bill: “Yeah, I didn’t have time to write mocks for the database layer, so we just use a real database.”

Have some spice 🔗

The time has come to introduce you to my philosophy on unit tests. Well, at least inasmuch as unit tests relate to databases.

We are backend developers. 50 percent of the code we write takes data from an HTTP request, fiddles with it a bit, and then saves it in a database. The other 50 percent of our code takes data from the database, does some fiddling, and sends it back to the client in an HTTP response. You know, give or take a few percenties.

Here’s my hot take:

The “fiddling” bit is the only part worth unit testing

Here’s where I really disagree with Bill: I actually prefer his tests that run while connected to a real database. Though I’d more prefer integration tests that run separately from the unit tests… At least with a real database I’m testing code that actually runs in production.

Mocks are perhaps one of the worst things to happen to backend development. And don’t forget, we allowed JavaScript to run server side.

I hate mocks because they:

- Don’t test code that actually runs in production (which means they don’t…test…anything?)

- Give a delightfully false sense of security (management loves this)

Okay smartass, how do I test my HTTP handlers? 🔗

Sorry to say it, but… have you tried writing better code? That sounds rude, and it is. But these articles are only fun to write if I make them snarky. I’m nice irl I promise.

Take a look at the following function:

func saveUser(db *sql.DB, user User) error {

if user.EmailAddress == "" {

return errors.New("user requires an email")

}

if len(user.Password) < 8 {

return errors.New("user password requires at least 8 characters")

}

hashedPassword, err = hash(user.Password)

if err != nil {

return err

}

_, err := db.Exec(`

INSERT INTO users (password, email_address, created)

VALUES ($1, $2, $3);`,

hashedPassword, user.EmailAddress, time.Now(),

)

return err

}

There’s no way to test this function without a database connection available at the time of testing. I can practically hear Bill brew installing Postgres as I type.

My humble argument is that the database logic, this part:

hashedPassword, err = hash(user.Password)

if err != nil {

return err

}

_, err := db.Exec(`

INSERT INTO users (password, email_address, created)

VALUES ($1, $2, $3);`,

hashedPassword, user.EmailAddress, time.Now(),

)

return err

Should be tested in an integration test. (or, _ gasp _ manually). However, this validation logic can easily be tested in a unit test. You know, this part:

if user.EmailAddress == "" {

return errors.New("user requires an email")

}

if len(user.Password) < 8 {

return errors.New("user password requires at least 8 characters")

}

It’s critical to remember one of the key tenants of software engineering:

Your code is ass

And because your code is ass, you shouldn’t be scared to make some changes! Sure, this function will “require” a database connection to be tested:

func saveUser(db *sql.DB, user User) error {

if user.EmailAddress == "" {

return errors.New("user requires an email")

}

if len(user.Password) < 8 {

return errors.New("user password requires at least 8 characters")

}

hashedPassword, err = hash(user.Password)

if err != nil {

return err

}

_, err := db.Exec(`

INSERT INTO users (password, email_address, created)

VALUES ($1, $2, $3);`,

hashedPassword, user.EmailAddress, time.Now(),

)

return err

}

But what if we break it down into… mhhmmmm what should we call them… “units”?

func validateUser(user User) error {

if user.EmailAddress == "" {

return errors.New("user requires an email")

}

if len(user.Password) < 8 {

return errors.New("user password requires at least 8 characters")

}

return nil

}

func saveUserInDB(db *sql.DB, user User) error {

hashedPassword, err = hash(user.Password)

if err != nil {

return err

}

_, err := db.Exec(`

INSERT INTO users (password, email_address, created)

VALUES ($1, $2, $3);`,

hashedPassword, user.EmailAddress, time.Now(),

)

return err

}

Aha! Now we write a neat little test:

func TestValidateUser(t *testing.T) {

err := validateUser(&User{})

if err == nil {

t.Error("expected an error")

}

err := validateUser(&User{

Email: "[email protected]",

Password: "thisIsALongEnoughPassword"

})

if err != nil {

t.Error("should have passed")

}

}

We’ve tested all the validation logic that we would have tested in the original function with a mock, and now we don’t need to, you know, write a stupid mock.

Mocks cause blocks

Blocks cause talks

Talks about mocks with devs are cocks

Bugs with shrugs come

Bugs with lugs come

Lugs writing bugs with mighty shrugs come

Look here. Look here. Mister dev dear

Let’s stop the mocks that cause the blocks here

We can test, and we can nest here

But we don’t need to mock the rest here

PS: I have a new Go course that you should check out. It’s pretty alright. I promise.